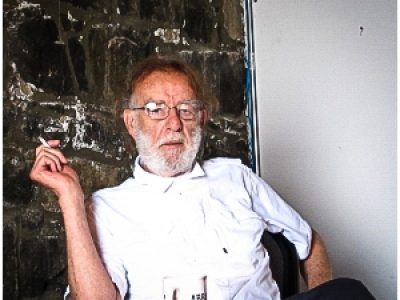

Neil Robinson

Neil Robinson – punk vocalist, squatter and food grower

autumn 2011

—

[ introduction ]

I’ve heard it said that one of the hardest distances to bridge is that of the distrust between two strangers.

As the afternoon sun began to settle, we had finally weeded the last of the kale beds, pulled some of the last of the season’s beets, and cleared what we could of the overgrown tomato plants inside the sweltering greenhouse. We had awoken at some ungodly early hour to get here to help out for a day. The tinny music of a simple crank radio wafted through the air, provided it was positioned just right and could pick up a signal out here, a ways out of the city.

Talking with friends, I’ve found that, for better or worse, who we are when we are 14 or 15 seems to determine who we are at twice that age. At 14, I recall being a nerdy introvert who used to ditch school to read books in the park and listen to third-generation punk cassettes of bands who sang about issues that the high school me was hearing for the first time – issues that I would later begin devoting a lot of my own energy to.

The farm belonged to the Farmegeddon Collective, a group of more radically-inclined individuals who produce food for some of Portland’s more non-hierarchically run restaurants and co-ops. Neil – who sang on some of those old punk cassettes – is breaking ground on other rows that will be prepped for winter crops, in between coming over and catching up on the past several years since our paths stopped crossing with any frequency.

The urge to create a better society takes form in many smaller interactions – working toward healthier relationships with other people and species, healthier land and food, and the combatting of those forces and institutions that build barriers to these goals – and encompasses both creative and destructive tendencies, though often it becomes easy to develop a fixation on one to the detriment of the other, or to find it easier to just stop swimming against the tide altogether.

Neil is probably better known for the bands that he has been in (Nausea [the recordings with his vocals recently anthologized on Volume 2 of the band’s Punk Terrorist Anthology], Final Warning), the diy record labels he has run (Squat Or Rot, Tribal War), or for his participation in New York City’s squatters’ movement and ABC No Rio show space. However, for the past several years, his main activities have been his role as a produce buyer at the natural food store, People’s Co-Op, and more recently, working with a small group to cooperatively operate a certified organic farm on the outskirts of Portland. I have sat with him at neighborhood association meetings, eaten restaurant-calibur meals he’s helped cook for Food Not Bombs, seen him coordinating book distribution tables at the punk shows that he has helped set up, and sat on porches discussing the gap between community-based goals and community-based actions. He has always struck me as being a person less apt to align himself with scenes and identities than to try to engage in ways that seem most consistent with his personal ideals.

As time goes on, those ideas I was coming across at 14 or 15 seem less and less radical, and increasingly… common sense. What seems radical is the extent that habits, trends, policies, and riot police will discourage and fight against any sort of positive change to these patterns, regardless of how destructive and unhealthy we realize them to be.

When I recently heard that Neil had sold his record collection – the records he had made his living off of, the bands he had taken on tour and booked shows for, the bands that he had been in himself – it made me consider where one sees one’s self if punk music shaped a lot of their ideals, but at some point you realize that those ideals pertain to a lot more substantial areas of the world than simply music.

After spending part of a day working on the farm with he and others of the collective, Neil sat down with me outside of the Red And Black Cafe, one of the collectively-run restaurants the farm supplies to. What follows are the recollections of someone who has spent the majority of their life attempting to bridge those disparities between strangers.

—

[ interview ]

Neil Robinson: …I pretty much got into punk through my brother. One night, when I was meant to be doing homework, I went into my brother’s room, he had this record on the record player, it was the Sex Pistols, Never Mind The Bollocks. And I put it on, and put the headphones on, and, BOOM, the minute it hit the first song, I was just drawn in. The lyrics, I mean I could pick out certain words that were in the songs, and it just spoke to me. It was around ’77, so I was maybe 13, 14. Before that I had been listening to 70’s kinda glam, pop music. Mud, Slade, Gary Glitter, all that type of stuff. I took it off, and I said, ‘wow!’, you know, and that night just totally changed my life.

A couple weeks later he picked up the Clash album, the first one. I think even then I was aware of the difference between what the Clash were singing about and what the Pistols were singing about, and reading the lyrics, because they had lyrics with theirs and the Pistols didn’t. I remember really resonating with the Clash, the whole I’m So Bored With The USA and London’s Burning With Boredom, I’m reading the lyrics, I didn’t understand them all, but this really spoke to me. And their songs around diversity issues. I worked with my dad on building sites in London and I saw the way certain people got treated by other people in terms of both class and race. This was the time of Apartheid and Ireland, and from an early age my dad had always instilled in us that everyone is the same. My dad had eleven brothers and sisters, and one of his sisters lived in Johannesburg, South Africa. And I should never forget the one day she came to stay with us. My dad hadn’t seen her for years. And the the first thing she said, she walked in the house, and she asked my dad where our niggers were. My dad’s like, ‘excuse me?’ And she says, ‘oh, in our country, everyone has a nigger.’ Like a slave. And my dad just kicked her out, and never spoke to her again.

It was interesting then working on the building sites, which were made up of Irish and recently emigrated Blacks, a lot of people from the West Indies, and hearing the big media stories about Apartheid, stories about Ireland, and then being with these people and hearing their day-to-day stories. Even back then I realized you need many sources to get the real news because you’ll hear the stories, but then you’ll hear from the person who has to live it everyday.

Later my brother was going up to London. X-Ray Spex and the Skids playing at the Marquee. My mum wouldn’t let me go, but I snuck out the window and went up there with em. I’d took a garbage bag and I had cut holes for the sleeves, I was wearing a garbage bag [laughs]. The funny thing is I don’t remember the show. We were in the show, it was packed, at this time I was smoking cigarettes and I’d started drinking but I hadn’t really done drugs. They started passing round this big cigarette, I was like, ‘oh, yeah, everyone’s sharing this, I’ll share some.’ Took a big ol’ puff of it. It was hash, and damn, I totally passed out and missed the whole show. But going to that, experiencing that energy, it was just incredible.

And then school was going terrible. I was trouble-maker, I had learning disabilities. And a couple of months later, Sham 69 came out with Tell Us The Truth, and I took the album into school. We used to have a recess time, so I set up a record player, and I put it on, I put on Borstal Breakout, and ALL the kids were going crazy, and the teachers were trying to turn it off. There was like a mini riot, and I got expelled… again. Oh, that was hilarious. And that was again, you know, the Clash and the Pistols, and along came Sham 69, which, classwise, even though later they later became synonymous with right-wing attitudes, at the time it was more, ‘oh, they’re not just singing about the street, they live on the street, they dothe stuff they’re talking about.’ Whereas with the Pistols, it just seemed all fake, and the Clash I started hearing about that they were pretty well-off youngsters.

And then I went and saw Sham 69 in the East End. I hadn’t really seen skinheads like that, I was really intimidated by them. Like tattoos saying ‘Made In England’ on their foreheads, or tattoos around their neck ‘Cut Here’. Damn, that was such a violent show, but it was so amazing.

Maybe a year later, at 15, I managed to get a job up in London working at a hotel chain in the kitchen, which was a time when the unemployment was raging, there were 1 in 12 people unemployed, youngsters mostly. At our school they were really only trying to teach kids how to sign their names on the unemployment check, because there wasn’t much hope that you were going to get out of school and get a job. A lot of my friends were joining the army, of that bunch, one was actually real sad he joined up. First, getting out of basic training, he went over there, he was out on patrol, and walked around a corner and there a kid with a toy gun pointed at him, and he shot. He didn’t shoot the kid, he managed to miss, but it totally freaked him out. Of the other jobs that people were taking, I was looking at going to Saudi Arabia and working on the oil rigs. I don’t know how I managed to get a job. So I moved up to London.

I was going to the 100 Club and to the Marquee pretty much every weekend and seeing your mainstream punk bands. I was mainly into drugs and alcohol, I was living in a mixed-age hostel owned by the hotel chain. This was in the Maida Vale area, and up the road from us was a squat. I had seen these anarchist symbols and that through the Pistols, but not really any political ideology behind it, and I started seeing these people with anarchy symbols and vegetarianism info and and this and that, and I started talking with them. At the same time I was traveling on the tube to get to work and there was one time I went in in the morning and every tube station had this painted stenciled logo, and it’s all over, on the station, all over the trains. I’d seen this logo, some of the squatters had this same logo, so I was like, ‘damn, what is this?’, you know? And I started asking around, and it was this band, Crass. A couple weeks later, there was a show at a big squat on the Old Kent Road, it was Crass, Flux of Pink Indians, DIRT, Zounds, all of them were playing. And seeing all the banners hanging behind the bands, being someone with ADHD, I had a hard time just staring at someone singing to me, if they had images, it really drew me in. And fucking Crass comes on and they got a film going and having soundbytes, I thought it was so incredible. And Steve could explain the songs on a level that most people could grasp something, you know? I had started meeting some of the more intellectual anarchist crowd and I was lost when they were talking, it was like ‘oh, here we go again, another intellectual, just like my teachers, talking to me as if they’re an authority figure.’ And then Flux, they were the band where I picked up the whole veganism / vegetarianism / animal rights, they had an information packet from BUAV, the British Union Against Vivisection. When I read that, that was it, it was like, vivisection is just wrong.

I was at a show and people were talking about how they were gonna go out to the Crass house, Dial House, in Epping. There was an open-door policy there, anyone could come stay. I went out there with a group. It was cool, people would sit around talking politics, some people would be out in the garden. But again, I felt very… I didn’t understand a lot of the stuff they were talking about, so I had this feeling, ‘I don’t belong here’. And I was hanging around with skinheads who had nationalist ideals, and I knew I didn’t belong there. So I was kinda stuck in this middle. I just wanted to find a band that kinda spoke to me. I was also working a lot, I mean a hell of a lot. I was doing a lot of drugs. Working in the kitchens, I got pretty heavily into… plus in the punk scene then, it was speed. Every weekend we were speeded up. I’d hang out a lot at Notting Hill Gate, and that’s when I started hanging around the Rasta pubs, because I was getting hash. One day someone asked me where I was going to get hash, and I said down to St. Stevens Gardens, and they said, ‘what?! You’re walking around there? White people can’t go there.’ I started seeing how people’s perceptions are, how they’d put up these barriers. And I’d go to the pubs, and I’d sit with these old, old Rastafarians, with big ol gray dreadlocks, and they’d smoke me out. Then I worked with a couple of Jamaicans in the restaurant and after work they used to take me to the after hours parties, and everyone’s just stoned, and I’d listen to reggae and dance. I’d done that for a long time, so I really liked when the Clash started mixing in some of the reggae, and later when Nausea wrote the song about Peter Tosh, it was definitely drawing on the influences of growing up in the Jamaican community and the influence of reggae.

I’d started going to demonstrations. I went with Flux to a demo, and that was my first experience seeing that all these bands were being followed. It was an anti-nuclear demo where we were going to a silo outside the city, and this van followed em the whole way. Hanging out with Crass, it was the same thing. This was during the time when Crass had put out that fake phone recording of Thatcher and Reagan, and that had really blown up in the media. They didn’t know it was Crass at that point, I think they thought it was Russians. So when that came out, punk was still, ‘ah, they’re just layabouts, they’re never gonna do nothing,’ then all of a sudden it was just, ‘whoa, we gotta watch these people.’ I think the more mainstream punk at that point did completely separate from the more anarchist, revolutionary style of music and lyrics, I think you saw a real separation then.

At that point, did it feel as if the anarchist punk movement was being seen by the state as an actual threat, or was it just a smaller isolated scene?

No, it was a threat. I mean, there were squats all over town. The Animal Liberation Front had started doing stuff. It wasn’t the ALF then, back then it was Band Of Mercy. Anyway, the ALF was getting in the media. I think the media did an amazing job of building it up. I think if they hadn’t started reporting on these actions, I don’t think people would’ve heard about it. But I remember the first laboratory got broken into and smashed up, And the thought of those beagles finally having freedom, it was an intense feeling. And then there were weekly protests against the laboratory, and hunt sabbing started, so I was going on hunt sabs. They were hunting fox and grouse, mainly fox. My mum and dad, they had moved out of where I grew up and out to a little village that had a hunt. The head of the hunt lived down the road from them, so we’d done some stuff down there.

The hunt kinda had free range to go wherever they wanted. But some people in the village didn’t like it. One time they were tearing through my dad’s garden, so he went out there with a cricket bat, and, ‘boom’, he hits one of the huntsman off his horse. He had to go to court, and the judge let him off. But it was very much a class thing again.

Around this time in London, we got kicked out of the place we were living off Kensington High Street, and the whole group of us moved out to Sudbury Hill. We had your classic punk house, I tell everybody if you’ve ever seen The Young Ones, that was our house. We had a fireworks display for Guy Fawkes Night in the house. I’d come home from work and they’d all be completely stoned. The television goes off at 10 o’clock back then, they’d be sitting in front of the TV, there’d be nothing on it, but they’d be all… [looks stoned and comatose]. We’d go out, get trashed and then take the tube home at night. That’s where we’d get into trouble. We hit that point where if you were a skinhead, you were the enemy, and if you were a punk, you were the enemy. So whenever you saw a skinhead, you’d usually get into a fight. There was this one time, [laughing] it’s the last time I ever drank whiskey. I had drunk a bunch at the pub, and I came out and all my buddies were behind me, and I saw this one skinhead, so I steam at him, and ‘boom’, punch him. He’s got 15 buddies all upstairs, so they all come running down, my buddies caught up with me, but by then I had already started getting a beating. The last thing I remember is I saw the front of a steel toe cap boot, smashed me directly in the nose, split my nose. And then I woke up on the train, they’d pulled me on the train, there was blood all over me, but we were singing away. It wasn’t until the next day when the alcohol wore off that I started feeling the pain. After that I never drunk whiskey again. [laughs]

Can you talk about when you initially came to New York, and what led you to relocate to the US from England?

I met this American girl one night, Jennifer, and we started hanging out. She was leaving, and we kept in touch. I would go to a phone box down the road from me at a certain time, and she would call collect, back then they didn’t have a computer system that would let them know, and we would be on the phone for hours. Sometimes the operator would come on, ‘excuse me, are you on a payphone?’, ‘no, no, this is my own phone.’ I had gone to another job and it was really stressful work. I was doing split shifts, I’d work in the morning and do the lunch service, have a few hours off, and then go back and do the dinner service. I was shooting so much speed to keep me going. She came back a few different times to see me, and, it was the day before she was gonna leave, she asked, do you want to come to America?

What year was this?

83. We started off in New Jersey, where she was living. We were going into New York a lot to see shows and that, so pretty soon we started looking for a place in New York City. She was going to NYU, she managed to get me in the dorm. This was Rubin Hall, right by Washington Square, and Dave from Reagan Youth lived downstairs. He’d come up and we’d talk politics for hours, and I really liked Reagan Youth. That’s how I met Vic, he was in Reagan Youth, and he would become the guitarist for Nausea. While I was there, WNYU had the best punk show. Jen was friends with the DJ, he was the last person you’d look at and think punk, but he knew all his shit. So I’d just go sit with him and get to know the bands because the bands that were coming through, he’d play on his radio show. Around this time I was starting to hang out at CBGB’s.

Then we kinda got tired of the dorms, and she was about to finish college. We got an apartment above Downtown Beirut on 1st between 9th and 10th. Downtown Beirut was thepunk bar on the Lower East Side. That’s when I started meeting the people that were squatting on the Lower East Side. And I started a job, I’d get up at 4 o’clock and go down and sit outside this moving company, and the owner would come out and go through the line and pick out who was going to work that day. I got in with this African-American guy, Freddie. He was kinda a mover-by-day and then a hustler at night. We’d often go out together at the end of the day and I’d make way more money hustling pool or whatever we could pull. He introduced me to dealing coke. And I wasn’t making enough at the job during the day to make the rent. I hadn’t really started dealing yet, I was kinda helping him do stuff. But then Jen and I split up.

I got another job at a restaurant, and my buddy was squatting the attic at this art gallery down off the Bowery, just over from CBGB’s, and said I could crash there. I was there a few weeks, then the owner of the building found out we were up there. I think he knew, but he let us go, but then he came up one time, and he said, ‘you know, I got that empty apartment that’s being renovated, do you all wanna live there?’ We were like, ahh, there’s gotta be a catch, so he said, ‘if you’d be my runner, I’ll let you live there.’ He was running coke. So I started working for him. I’d be going up to midtown and down to Wall Street. That was my introduction to how much drugs go through the Stock Exchange. It was incredible, nearly every fucking broker was high. That’s where we first started the band. I remember we started doing Black Sabbath covers, that’s kinda how Nausea begun. And then I was at CBGB’s one Sunday and John came up to me and he was serious, he was like, ‘do you wanna sing in a band we’re starting?’ I’m like, shit, yeah!

At the time, I was kinda hanging around with the Yippies, they had a building across from CB’s. They didn’t do much other than get stoned, by then I was much more into uppers than downers, but they’d do some cool stuff like die-in’s uptown, and they always had lots of literature there. I think that’s where I heard about a squat that a group of people were going to be opening up on 8th Street between B and C. I wanted an environment that was more political than the place I was at, I wanted to be around people that had values for building community. So 8th Street opened up and a lot of punks moved in. It was kinda right at the time when every empty building, people were opening up.

It wasn’t common for there to be a political slant to a lot of the squats happening?

No, the squats that were there were there out of necessity. At the time I got there, the Lower East Side was a classic war zone. Drugs were just being dealt out of every abandoned building. Cops weren’t allowed to go past Avenue A or 1st Avenue without two being in the car because if they stopped and got out, they’d jack the car. I think that’s why, early on, they kinda allowed the squatters to go in, because all the abandoned buildings were being used by drug dealers. I mean it was incredible, you’d have a cop car parked over there, and there’d be people outside a building just lined up, with a brick that would come out of the wall, and right there were the cops, they couldn’t do nothing. So drugs were rampant in the whole neighborhood. There was definitely a lot of violence. I realized there were set turfs, it was drug related, and it was interesting when I started working for Puerto Rican dealers, I could go between all the different turfs. I think that’s why all of a sudden they allowed other people in, it was helping their business.

At the time there was this warehousing law, a landlord could buy a building and they could leave it empty and they would get the fair market value tax break. So most of the buildings were structurally okay, but then they’d buy em and have local kids set fire to them so no one would be able to live in them, and then they’d get a tax break. So there was no incentive for em to do em up. The city was kinda looking after em, for keeping them empty with a vision of… and I really didn’t, at that time, have a long-term vision of what it meant to warehouse all these buildings, I really didn’t understand gentrification then.

How large of a scale was the squatting going on at the time?

It was big. On 8th Street, there were like 5 squats, just on our block. We were right around the corner from Christodora which became synonymous with the Tompkins Square Riots, and Christodora was the first building that got slated for gentrification. I think that was really when the whole community came together, because they started realizing what it meant for everyone. You know, the Puerto Rican and Dominican community was very strong, you had a lot of family groups living together, a lot of people lived in rent-stabilized housing. But it became very apparent as 1st Avenue changed, businesses changed, and then when Avenue A businesses started changing, everyone was like, holy shit, this is not gonna stop here.

How did the environment, specifically, play a part in influencing the Nausea’s music?

So we were opening buildings, There were protests. The animal rights stuff, it was very different living in New York City than in England, it wasn’t like there were laboratories everywhere. There were hunt sabs starting out in Long Island, people were doing stuff out there. But the Lower East Side was a real tight-knit community, and it felt like it was under siege, so, really, our focus was to protect this little enclave of mixed-race, mixed-income community. Around that time, my friend got me a job working at this after-hours nightclub, Save The Robots. I got a job picking up cigarette butts and cleaning toilets, I ended up working there for ten years, I kinda became manager of it.

It seemed like you took things in a direction that not many other bands did – at least not many who have remained remembered through today in punk – was there anyone else who were coming from a similar place? Where did this direction come from?

It came from mine and their roots in English anarchist bands mainly. At the time it was mostly New York Hardcore; Agnostic Front, The Cro-Mags, and then the straight edge thing was really kicking in with Youth Of Today and Sick Of It All and those bands. It was interesting because we would play with all those bands, but with a very different message. We were definitely influenced by a lot of what was going on in England, and even bands over here, A.P.P.L.E. was around, Crucifix.

You weren’t a part of the band’s later recordings…

Back then, I had this thing, all our shows had to be benefits. That’s why I left the band, every single show we had done had been a benefit for something, and at some point, I didn’t really understand my economic privilege around having a job at the nightclub; it was a fairly flexible job and I only worked three days a week and I had it really well financially, so I would often foot the bill for the rehearsal studio and stuff. At some point we started getting offered money for gigs and at rehearsal one day someone said, you know, we should start taking money, and I said, No! It’s gotta be all benefits. And we had a big argument.

Was anyone else on your side with that, or was it mostly you against the rest of the band?

I’d say it was me against the rest of the band, because… I was stubborn then, and I couldn’t find the middle ground of, oh, we could take this portion to put into the band and then this portion can go into whatever benefit we want to do. It was like one way or… Which, years later, I regretted I wouldn’t see that.

Did you stay on good terms with the band when you left?

Fairly… I don’t know, I was pretty mad at the time. I was messing with a lot of drugs.

Was there ever a point where, as a political band, you sobered up, maybe the way Crass did, or was the drinking and drugs sort of a constant?

[pauses for thought] I think it was just kinda a constant through. You know, we were definitely aware of the issues of some of the alcohol companies, but we didn’t act on it. It was very much part of the culture then that, during the day, we’d go out from the squat, we’d hang out on 8th Street or on St. Mark’s Place, panhandle, get some money for pizza or some 40’s, and go down and sit in the park, maybe fall asleep in the park. And there was really a whole culture around Tompkins. I think that’s why when the Tompkins Riots happened, there was such a culture around it. It wasn’t just a park, it was its own little community. There was the punks, the homeless, the characters of the Lower East Side, it was their home for the day, and often at night.

It was a really interesting time, because I try to go through my head, how did I… I had these strong values and these political ideals, but they all were kinda mixed in with this, fuck, total nihilistic drug alcohol life, and how was I sortin it out in my head, like… to this day I can’t figure out, like… at some point I knew I had to get out of the drug game, you know. At this point I was still working at the nightclub. I don’t think I started dealing when I was in Nausea. I was a user in Nausea. And that was when I stopped, my heart gave out one time, and I’d been up for… I’d been on a speed binge for a week, I hadn’t slept. I got up one morning and my heart stopped. It was the scariest thing. And I went into the emergency room, and they were like, oh you had a heart murmur, or something, how long have you not slept? I told them and they were like, you gotta get off the speed and the coke. I mean there was a dealer next door to my friend’s squat, and we’d go there, we were paying $75 a gram, and we’d buy a bag. I would cut it again and I was selling mine for a hundred a gram. So we’d be in there, we’d be spending $500 a day, we’d just sit in there for hours smoking one after another, and then finally go to work. And it just hit me, that this is wrong. You know, to get sucked down to this level. And when my heart stopped, I was like, okay, this is it. And that day I gave up drugs, alcohol, cigarettes.

At the same time, you were involved with projects that were going in a lot more positive directions. After Nausea, you were doing record labels and helped start Food Not Bombs, but I think one of the projects I knew you had a lot of involvement with that is still carrying today was the ABC No Rio space. Could you describe the early stages of that space?

ABC kind got started with Mike Bullshit. He was in SFA, Spastic Farm Animals, and had come out, and at that time, openly coming out in the scene on the Lower East Side was kinda risky. CBGB’s was a really violent scene, it was extremely homophobic, and he was kinda sick of the violence at the Sunday shows. Every week there were stabbings. In the past, violence had always been outside of the hardcore punk scene, and all of a sudden at some point there was kinda a crossover where the popularity of the music and the scene had kinda pushed out, out into Queens, out into Brooklyn, into way more mixed neighborhoods, so all of a sudden you had this total mix going on and with that came some of the violence that was in those communities. So Mike didn’t feel safe. And at the time you were also getting a lot of younger Jersey kids who didn’t feel safe at CB’s. So Mike broke off and found this space, ABC No Rio. It was an arts space and they weren’t doing anything on one day of the week, so he asked them if he could do shows. What year, maybe 88, 89, 90, it all blends. He’d been doing shows for a while and I started hearing about them. I had started doing Tribal War by then, maybe it was Squat Or Rot back then [two diy record labels], and I went and started setting up the music. The bands played upstairs then. No violence. Lots of people just acting idiotic, or they could look completely normal, but it was safe. It felt really good to be there after CB’s. And I started going there fairly regularly, and it was a different scene, cos no one looked like me, they didn’t have the overtly punk… they didn’t have the uniform.

ABC was also a part of the squatting movement that was going on at the time, right?

The original art space, and I think it’s really key to have the background of how this space got going, a group of artists, who even in the 60’s and 70’s started seeing gentrification of the Lower East Side, got together and they put on an art show in an abandoned building. They had found this building on Delancey, and they had called it the Real Estate Show, and they wanted to get a message that these big uptown landowners were buying up the community and it was going to be at the detriment of the longtime community members. So they done this show, it was basically a squatted building, and the city had the cops come and padlock it, padlock the art show that night after the opening, because the opening was really big. The next day, they put together a party outside the place, they called up the media, there were some famous artists in the show, so the media was there talking about how these famous artists had their art stolen by the city. The city got real bad media, so they let them go back in, and they had the art show for about a week. Then, the city basically approached a group of the artists and said, ‘we’ll give you a building, we’ll give you an art space a block away, if you move out of this building.’ And that’s how they moved over to ABC. The reason it had got the name ABC No Rio was just across the road there was a lawyer’s office, and in Spanish it was Abogato Notorio, but the letters had fallen off and it just read ABC No Rio.

The city tried from the very beginning not to allow them to stay there. It finally got to the point where, this is just before I became involved there, the city was doing some work to a building next door, and there was a construction digger, and he said ‘accidentally’, but he smacked through the brick wall, the support wall outside our building. There were tenants living upstairs at the time. The city came and looked at, condemned the building, and they moved all the tenants out. But the art group would not go. They brought in their own structural engineers, who said it was a pretty easy fix. But the city was really trying to get them out. The city had been the biggest landlord, especially of low-income housing, and they were losing a lot of money because of it. So at some point, someone in the city said ‘we got to get out of the landlord business. Let’s just sell em all off.’ That’s kinda how in the Lower East Side, so many buildings got sold off to uptown developers. And ABC was one of the few buildings they were still trapped in because people were living there. So they couldn’t do anything until they got everyone out. They did things like the heating system would go off during the winter and they wouldn’t come fix it, the pipes would burst.

We started doing shows. We started allowing people to live upstairs, we figured if we squatted the building, it would make it harder for… sometimes at night people would come and they’d get into the building and electric wires would be cut. Just weird shit. We thought it was people from the city. They would come, they’d break our padlocks off and put their padlocks on. And I’d go and break theirs off and put ours on. So we figured we need people in here all the time. We put extra gates up, cemented up all the windows to the basement with cinder blocks, just really fortified the place.

Later, Mike was moving to a queer community down south, and Freddy Alva who’d been involved helping book shows with Mike called me up and asked if I was interested in booking some shows. And we wanted to move shows downstairs, it had an awesome basement, but it was a mess. So we went in there one weekend and completely cleared it out. We went to every dumpster in the neighborhood and filled them up. We installed a PA, built a stage, and then there was that one pole right in the middle in front of the stage, and we wanted to take it out but it was kinda the main support for the whole building, so we were like we better leave, and it was always there everytime a photo was taken. All of a sudden, I had booked Offspring, NOFX. Green Day was one that I booked and then they didn’t show up. They had approached us, and I guess their booking agent had booked three shows on the same day and picked which would be the most popular and didn’t tell us. I remember us getting together and I said ‘that band’s never gonna play in this state again.’ [laughs]

We started having really popular shows. I think the most we had was 700 people at a show there, I mean, they weren’t all in the basement because you couldn’t fit everyone in the basement. It was incredible. The sweat was dripping off of everyone. And the energy was amazing. Just that feeling of… it was DIY. It was a group of young people who got together and said, we don’t want businesspeople running our scene, we wanna run it in a way that’s got value and meaning, and any people can get involved. The first thing people would see when they came in was that ‘Leave your machismo at the door’ that someone had spraypainted.

And you eventually left ABC and New York and moved to the Pacific Northwest?

I left there in 97. I had heard about this place, the Liberation Collective, they had a little office in downtown Portland. They had a motto, ‘Linking Social Justice Movements To End All Oppression.’ It rung out for me because by then I was not single-issue focused. I was linking all the different pieces of the politics, beliefs, and values I’d experienced, and everything was intertwined. I saw that, and it just resonated. And I’d wanted to get out of New York. The Liberation Collective, there were people putting on demos locally. Portland had the Oregon Health and Sciences University, one of their primate laboratories was out in Beaverton, so there was lots of organizing around that. At the time Craig Rosebraugh was one of the main people, and he had been in a few punk bands. But he was very passionate and a great speaker. You sat down with him and everything he said made sense.

I met you on the Primate Freedom Tour, when you were touring with bands and speakers as a complimentary component to a cross-country activist tour targeting primate research laboratories. And I remember you were touring with not just Aus-Rotten, Anti-Product and Harem Scarum, but also with Mark Bruback, Sarah O’Donnell, and Fly, you were incorporating speakers and activist literature, and that’s not really the typical punk tour at all. Was there anything specific that motivated you to include different aspects to the shows?

I think touring with bands, it wasn’t like we were all one scene. There’s this impression that punk/hardcore is all the same. it’s definitely not like that, there were definitely different communities that had different styles of touring, of how the music was presented, of how the shows were presented. I’d always been open to trying something new. And people in New York would criticize me for putting the craziest bands on the same bill. I just wanted to bring people together and try and have them hear a different way to present it. Mixing straight edge bands with completely fucking drunk Casualties-type bands, and it was fun to see where it would go and how people would react. Touring with bands like Avail, they were not just your everyday anarchist-dressing tattooed… well, they were tattooed, but had really good lyrics, some of the similar struggles that everyone else faces day to day, but when they played their shows it was just a different vibe.

The idea of that tour was to raise money for the activist part of the tour, and also to kinda activate from the punk anarchist communities who had already been kinda doing stuff around animal rights issues in those areas, to hopefully get them out and onto the frontlines at the university demos. And I met Mark [Bruback] on a Citizen Fish tour. I had just gone to a show and Mark was doing his spoken word and I really enjoyed it. I had also met Sarah O’Donnell and I really liked her. And for something like the Primate Freedom Tour, it seemed really important to not just have bands screaming lyrics half the people couldn’t understand, but also have some time for dialogue. And again, I was pushing my boundaries. I had wanted to expose myself to hear what they were facing in their own daily lives. In Sarah’s case, being a young queer woman trying to play at punk shows, and Mark doing spoken word at these crusty shows with people completely abusing you. I was blown away because I know when I was performing, usually I would end up getting in a fight with a heckler, and Mark would totally turn it around and he’d use his knowledge and his experience of things to diffuse the situation and have the crowd laughing at the person that had started heckling. I didn’t want to just attract the punks, I wanted the activists that were already doing stuff in those communities to feel comfortable coming to a show, to offer it to everyone.

And I think I was getting tired of… I’d definitely started thinking about the fact that there were all these bands screaming about all this amazing stuff, but then in their daily lives they worked a shit fucking job for a shit fucking company, they drunk shit fucking corporate beer, they really hadn’t plugged into small-scale food sources. It wasn’t that I wanted to get sucked into judging or that but I was becoming aware of it myself, again, how all these different pieces are linked, you know? Where your food comes from, and the stores you’re shopping at, and with the meager resources I had I didn’t want to keep supporting them. On that tour, and I still think about this now, using a car to travel, flying around the world using up so many resources on one trip, and I kinda said to myself that the next time I fly, it will purely be to go back to Europe. It won’t be to visit or vacation or something. At some point around that tour – two months I think we were out – even though it was enjoyable, going to each town, meeting young people doing cool stuff, I wanted to be part of the cool stuff that was happening here. I wanted this sense of laying down radical roots and starting to lead by example. So after that tour, I was like I’m done with touring, I wanna lay roots.

So you recently sold your entire record collection – including the records of your own bands. After being involved in punk for so long, after having the distro which was livelihood, what made you decide you wanted to part with the records?

I had moved all those thousands of records from New York out here, I had moved them again from one house to the Mississippi Co-Op House where I did the distro out of the space that became the Black Rose Infoshop. And when I moved out of the Mississippi Co-Op, I moved into another house and I just filled up the rooms with boxes. Then I decided to move into an apartment at a co-housing eco-village, it was very small, one bedroom. I wanted to move into a space that I felt my impact was less because of the scale of the place. And I realized I couldn’t take all this music with me. I realized that there would be other young people that the message would have more value to than it did to me anymore. And all those images, all those record covers are all tattooed in my head anyway. The memories are all there, the music is still there. The values, the sentiments, all the imagery is all there. I knew at some point I would stop doing it and some other young person who had a passion would carry it on, plus I had started a farm, it would be nice to have that extra money, to invest that money into the farm.

Can you tell me about what led to your initial involvement initially with People’s Food Co-Op and describe your progression into eventually becoming a farm owner?

I felt like it was recently after the Vail action, the first big action that got national media attention around the burning down of a new ski resort in Vail [Colorado] that had pushed into lynx habitat. The Earth Liberation Front had taken responsibility, and the Liberation Collective put out the communique. All of a sudden the heat came down on everyone, and I hadn’t been working for quite a while. The forest movement was very strong here. And that was very influential on me coming from New York, you come to the northwest and you’re out there in pristine wilderness and you’re hearing the chainsaws and watching the trucks. So there was a lot of anti-logging action. Tree spiking was still happening. There were cop cars being burned in Portland. Concrete trucks were being burnt. Things were really escalating as far as… I still look at it, to me it’s still non-violent direct action, that whole thing is still… that really divided the movement and I think the establishment really relied on that divide and conquer, and it was kinda sad in those early days watching these mainstream environmental groups denounce… But things started heating up. And when the feds came around knocking, because of my status here, I was an alien resident, and as an alien resident, if you commit any federal crime you can be deported, I kinda felt like I might need to get a real job. And again, I wanted to set some roots and settle down.

And food was your particular interest with that?

I wanted to explore a little more subsistence, taking myself and the community I was living in out of the marketplace a little bit. I saw food access as a powerful tool, of both oppression but also a healing power. Around the Lower East Side there were many guerrilla gardens. A lot were started by Latino and Puerto Rican people, and I loved the sense of community around them in the summer, when people would go there and have barbeques. I remember the first time I done Food Not Bombs in New York City. I cooked at home and I made all these different lasagnas, and I took it in. I think it was a Saturday and I went into the park and we set up in the bandshell. Me and my partner, we walked around and told people we had free food. Damn! In the end police came to escort me out, because people were just so hungry that this power trip happened, some of the stronger homeless people who had just come out of prison, some people just started getting really abusive, trying to get the food, they weren’t being orderly. Next thing I know, people are fighting each other trying to get something, and then the police came and they’re escorting me out of there. But I saw the power in food. And then when I came here, sometimes I’d go down to the Food Not Bombs servings. And often it would be that the recently-freed prisoners would just come up and thank me for giving em such good food. They would complain that all they ever got in prison everyday was meat, and now they could eat this food, and the smile on their faces, I totally got sucked up into the power of food. And it’s becoming very apparent that both food and water access is probably going to be the fuel of the revolution, where people’s access is going to be the tipping point.

Can you talk a little about the nuts and bolts process you went through of acquiring the land, about what skills you did or didn’t have, and what knowledge you gain as a grower that differs from what you knew previously as more of a consumer?

I’d been helping a farmer for four years, he’d been a volunteer at People’s, and I volunteered with him at his farm. I started doing the farmer’s markets for him downtown, and when I was doing the market, I shared a booth with this Irish woman named Paula, and she was leasing land up where we are now. She was doing small-scale, just under an acre. She worked at an Irish pub three days a week and the other four days she worked on her farm, doing it all on her own. We shared a booth and she was growing beautiful produce, beautiful flowers, and we just talked. She inherited some land in Ireland and wanted to go back. At the time I was living at the Mississippi Co-Op and it seemed like the perfect way for the house to get involved in its own food production. I threw out the idea to them, and a few housemates got involved, a few people from the community got involved, and we just went out there and, you know, we had just kinda simple knowledge of doing food in our backyards, we’d read a few books. We’d done that first year and made a lot of mistakes, but so much food came out of it. We were putting stuff out on our free porch at the Black Rose, but there was still so much food. So we went down to the co-op farmer’s market and I went to one of the vendors and asked if she would mind selling some of the extra food we had. So for about a year I would take produce down there Wednesday mornings, and she would sell it for us. So we were producing food for our homes, giving some of it away, and selling some of it at the market.

After that first year, I was excited about the new way I could relate to farmers I was dealing with at People’s. I could talk to them about fertilizers and amendments they were using on their soil, the organic processes they were doing. I could talk about certain seeds, varieties. And I noticed as I was doing that, all of a sudden there was a new respect for me. Because I could talk to em, and I started understanding more about the issues of labor they faced. The migrant labor issue hadn’t really come out when I first started farming. And most of the farms I was dealing with, especially the larger ones, were using migrant labor. Migrant labor was the unopened can of worms that neither left nor right wanted brought out because there’s not a simple answer. But I knew the farmers I was dealing with paid them way more than the minimum wage. Even today we still talk about if we were to kick out all the Mexican workers, my friend, a Mexican farmer, always says, ‘oooh, you going to get the gringos to work?’. You work for 8 to 12 hours a day in southern California strawberry picking, whoo! I have this plan that every single American will work 8 hours a year in a field somewhere, because it’s brought me a whole new respect about the food that I eat, a whole new respect and appreciation. I understand struggles behind it, beauty behind it now that I don’t just take for granted. I know how many hours go into the garlic that’s being used in here. That garlic’s been in the ground for eight months. And I want other people to share in that appreciation of the food.

It’s interesting how little you ever hear the word ‘radical’ applied to food growing, in relation to other things such as diet, which is essentially consumption.

I watched that film, Power Of Community, it’s the film about Cuba after they had their food crisis. I really like the way that the government there really got the people to look at farmers as the leaders in their community. Here farmers still struggle to gain the respect that they should be getting. We leave them on their own. I mean the capitalist model they force us into is very much based on looking after yourself, it’s what perpetuates that. If we are really revolutionary, we need to come together in communities and we need to look after each other. And I think that experience I had in New York City living in the Puerto Rican community, in the Dominican communities, damn, the whole family looks after each other. Later in life, it’s really hit me the beauty that later in life the young person will be the person looking after the grandparents. It’s what they do. I mean look at what we do, we stick em away.

I was talking to someone earlier who moved from Portland to a farm in a smaller town on the coast around the time that I moved from Portland to a town with 8000 people. I always thought my town was a community, but I went down and stayed with her for a week and the difference was down there everyone was showing up for dinner with food they had prepared using ingredients from their gardens, from their farms, or had picked earlier that day in the wild. And I realized food is what makes community – your relationship to it. And my town was just totally disconnected, just is still urban, regardless of the smaller population. It wasn’t the size of the place the creates the community, it’s food.

For me, I really became aware… as undomesticated animals, there’s two things we have in all of us, to get food and shelter. They’re the two basest instincts we all have. So when someone tells me they don’t know how to grow food, I say, you may not know how to grow it, but I’m pretty sure if you were out in the forest, you somehow would know what was there to eat. And to find shelter, you put someone out in the forest, they’re gonna know how to make shelter. I started thinking a lot about the undomesticated experience we have, and I think this urban experience, like you say, I think they want to get us away from the knowledge of how to grow food. And if you look back many many many years ago, so many revolutions and so many conflicts arose around access to land and growing food. But things are shifting in Portland, and everywhere. I read about in New York City where they’re covering massive warehouse spaces and filling em with dirt, and filling boats with soil and putting them on the East River.

I think something you might have seen a lot of from music in the past and and also in the more recent efforts to really bring back a more sustainable environment around food is co-opting and greenwashing by larger companies. For instance, on the West Coast, there’s one company that now controls all of the distribution of packaged health food. Do you feel that there’s any room for only changing consumer habits, or do you feel like that might only be doing more harm than good?

You know, when I look at Hot Topic selling Nausea t-shirts with my Smash Racism logo, it pisses me off to no end. I think Chumbawamba tried to take that on: can you be popular with a simple message and can you control popularity. I do feel that the industry learned from the early days when they feared punk for going on its own, for doing the DIY thing. All of a sudden you had these major labels setting up these so-called DIY subsidiaries so that they would have street access, they kinda learned how to get in there and control it.

I’d say with food, people are aware, I would’t say the general public, but the co-op community, the natural food community that’s been supporting small natural food stores are definitely aware of the big chains plugging into it. You know, Wal-Mart rolled out their organic line, and now they’re even downsizing to smaller stores. Safeway’s doing it, and I feel like they’ve all started at such a late stage that people are wary of them and are not necessarily plugging into the prices they offer without knowing the issues that go into getting those prices. You know, at People’s we decided to stop carrying corporate sugars, because what we found out was a lot of these even organic corporations are destroying rainforests to plant sugar plantations. So we plugged into a company that does fair trade sugar. What we’re finding out is, especially on a global scale, demand for good quality environmentally- and community-rewarding food is higher than what can be sourced. Even corporate stores are plugging into fair trade. So now we’re at a point where we can’t bring in the fair trade sugar because there’s not enough of it being produced.

Another thing that’s going on is the issue with quinoa, in places in South America where quinoa is their diet, they don’t have enough for their own communities. They’re exporting so much of it to Europe and North America, they’re losing their cultural diet because they’re getting paid more than keeping it local. So there’s certain things people are starting to realize, they’re starting to link population growth, demand for good food; if you get a demand swing one way, we can’t fulfill that demand. Bananas are coming to an end as we know it, because all bananas are a clone, so what we’re eating right now is called the Cavendish banana, and there’s already a disease that’s starting to wipe out the Cavendish. Back in the 50’s, we lost the banana that was before the Cavendish, it got wiped out by disease. Well the next bananas are nothing like what we’re used to, there’s little finger bananas, and the red banana. So for me it’s the perfect time to bring up the local food discussion.

I think we all have the obligation to start finding land that’s on the outskirts of towns, to start purchasing that land, to keep it from being developed. It’s cool doing these small green spaces in the city, but you’re not going to grow enough protein from beans on a half-acre plot in the city. Now if you have a hundred acres on the outskirts of town, you could make a dent.

At the same time, though, the trend is more and more people moving into cities and urban environments.

You look at Europe, whereas the squats in the urban areas got busted, all of a sudden in France and Germany they’re going out of the cities and finding farm houses that had been abandoned for ages and starting communities. There weren’t any cops that really cared. They done a lot of work to get to know the neighbors, to work with them, and a lot of them have become really successful. I want to have those relationships on the edge. I need the urban environment. I need to be forced to socialize. I don’t want to keep pushing out. It bothers me that we have this easy convenient access to what we call the wilderness. We have this relationship where we’re either conquerors of the wilderness or we’re observers, and I’ve never felt this necessary need to escape and climb a mountain. I realize with the farm it’s taught me to sit and observe nature, because really all farming is is becoming a steward of what nature does. You know, nature was the first farmer. Conventional agriculture and even large-scale agriculture tries to take on nature by faking it, and I’m interested in permaculture, in, you know, can we let nature do its thing and grow the food, but there also be a commercial relationship. I feel like we’re kinda experimenting with that on our farm.

Understanding that people tend to struggle against the oppression that’s most directed toward them, such as being Black, identifying as queer or transgender, being poor, I think a lot of people don’t look at food as being a struggle. Do you feel like healthy food is something that can coexist with people’s more direct struggles, that food is something that people can actively dedicate energy to?

I mean good food access is definitely around class struggles. Every community that struggles with class is talking about it. People are looking at obesity issues, heart issues, why is it that the African American Black community has such high issues of heart disease, of cancer. And you can’t help but link it to the food that’s available to single parents, people on welfare or getting food stamps. You know, finally parents at schools are realizing that kids going to school and getting their food out of vending machines… The Oregon Food Bank here has its own farm, and people who are getting food from them are invited to come out. It’s both a demonstration farm and a food-producing farm. And then you’re starting to see where groups of people are coming together and say things like, ‘you see that piece of land over there that’s got the abandoned house? can we knock it down and grow food on it?’ Or there is a lot up in North Portland where they’re just taking over pieces of land.

I’ve been talking to a group that’s now working in the West Bank [Israel] to replant olive orchards along the border, and they’re looking for people from Europe and the US to go out because soldiers are taking potshots at the farmers. In Mexico, they’ve completely lost all their access to their ancient foods because the US put pressure on their agricultural system to grow stuff for export, to where they have no corn for themselves. They bring their corn in from America, and who grows it in America? Migrant laborers who had to come up here. And again, I think we’re at that tipping point where many communities are having to think about the access to food, where learning to grow food and learning about the food that’s already around us is going to be really important.

In your mind, what do you think it is that keeps people from doing anything about these issues, what is it that keeps people content and stagnant in their current habits? What do you think it would take to make people overcome those barriers and take an active interest in pursuing those issues?

I think the root of it all is the self-serving capitalist model, especially in this country. I mean you look around the world, and… I don’t know what to call it, socialism, communalism, cooperatism, on an international scale is happening; people are saying we want to work together. But for some reason this country… I still can’t help but… I know we need to be patient, this is a very new country still. I don’t think we realize how new it is, and I have definitely thought about these issues, especially growing up in newer communities of recent immigrants and my own personal experience of ‘this isn’t home for me.’ And when you start looking back on who can call this home, you realize this country’s made up of people that cannot call this home. Then you got this very strong rugged individualism. I mean unfortunately now freedom to practice commercialism also falls under the first amendment. It’s no longer freedom of religion, now it’s also freedom to consume. When you go out into the mainstream and you start talking to people, people get really defensive, ‘you’re gonna take away my access to that cheap meat?!’ I see that even here within the vegan movement, sometimes it feels like there’s that selfish entrepreneurship, just pushing their own success, and unfortunately it still feels like success is measured by how much money your business makes. Even at People’s we struggle with it because it was only when we started breaking a couple million dollars, all of a sudden the industry wanted to hear ‘how are you doing it? What are you doing that makes you money?’, but not really focusing on all the community building that goes behind what People’s is, forgetting that it started in 1970 and there’s still people who are owners who were part of the original store.

And maybe that’s one of the issues of punk, is that it tries to replicate, because when you try to replicate you’re losing some of the genuineness. Whereas if it’s a groundswell, if the music, the politics, the values, if it’s grassroots from within, you know, it has a genuineness that people can plug into. I think there’s also so many divisions, economic divisions, racial divisions, and I think a lot of people are trying to heal them, but then we have policies on a government level, on a state level, that still just perpetuate and keep those walls up. The English were good at it, and the US has learnt from it. So really, to me, until the capitalist model goes down, and then, we start working on mutual aid and building communities that really do care about everyone in the community, it’s gonna be hard. It’s gonna be very hard. That step from convenience and access to everything to having to make hard choices, I don’t know how that’s going to happen. But it will.

—

To find local growers in your area, go to LocalHarvest.org.

More information on the Farmegeddon Growers’ Collective that Neil is a part of here.

An edited version of this interview appeared in the March, 2012 issue of Maximum Rocknroll.

New York, NY – October 29, 2020: Basalt Infrastructure Partners LLC (“Basalt”) announced today that the third flagship Basalt fund (“Basalt III”) has completed the acquisition of a stake in a residential solar portfolio from funds managed by the Infrastructure and Power strategy of Ares Management Corporation (“Ares”). As part of the transaction, Basalt III and IGS Solar (a division of IGS Energy) have formed a partnership to expand the portfolio by funding the build-out of additional solar projects across the United States. The solar projects will be owned through a newly created entity, Habitat Solar, and operated by IGS Solar. This transaction is the first investment of Basalt’s third flagship fund.