Summit Tunnels

Donner Summit Railroad Tunnels

abandoned tunnels from the first transcontinental railroad route through the Sierras.

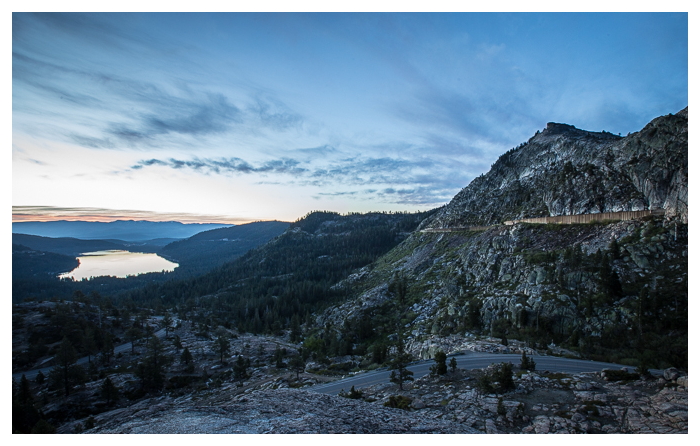

Just below Donner Peak in the northern Sierra Nevada mountain range in California lie the remains of the tunnels and snowsheds constructed for the first transcontinental railroad route.

In the 1860’s, the Central Pacific Railroad, in a race against Union Pacific, sought to complete the first transcontinental line. The heavy snows of the High Sierras required the construction of several miles of tunnels and snowsheds along the mountain pass, constructing 15 tunnels in all. (The difference between a tunnel and a snowshed being that a tunnel is a hole carved through the solid granite, while a snowshed has an outer wall constructed to allow the laying of a roof which would cover the track from snowfall.)

The most difficult and final tunnel to be completed was Tunnel 6, also called the Summit Tunnel, as the 1,659 foot tunnel straddled the highest point of the rail line. Taking over 15 months of excavation, Tunnel 6 had a vertical shaft in the center, allowing crews to work from the middle of the tunnel carving outward in both directions, while two crews worked their way inward from the ends. After completion, the deepest part of the tunnel sat 124′ beneath the granite’s surface.

Crews, made up predominantly of Chinese laborers, constructed tunnels, sheds, and walls that held up trackbeds, as well as protected tracks from snow. Aside from using only hand-powered drills and tools (the only mechanically-powered tool was an old engine used to hoist the debris out of the tunnel), these crews faced harsh conditions, with avalanches burying entire camps on several occasions.

The transcontinental railroad allowed for the first time the large-scale accessibility for passengers and freight to be transported across the Sierras.

In 1885, Southern Pacific Railroad took control of Central Pacific. Just a few decades later, in the 1920’s, Southern Pacific completed what they called Tunnel 14, a different tunnel that ran parallel to the first line about a mile south of the original set of tunnels. This new line – named Track 2 – was deemed to be easier, as the uphill grade for westbound trains was less than that of the original track.

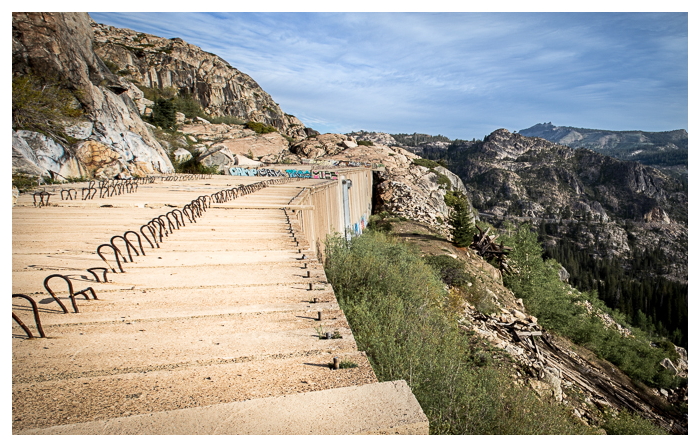

Over time, the original snowsheds, built from wood timbers, were replaced by reinforced concrete structures. Residents from the Summit area would often gather the old wood for buildings.

In 1993, Southern Pacific closed the Track 1 tunnels, and removed the tracks, opting to run railroad traffic on Union Pacific’s Sunset Route to save on costs. (In 1996, Southern Pacific would merge with Union Pacific.)

As the size of railroad containers grew, Union Pacific had to run double-stack container cars on the Feather River route to the north, as the traffic was too large to fit through the tunnels in the Sierras. Eventually, due to an increase in rail traffic, Union Pacific would lower the grade level within the tunnels, as well as cut square corners out of the arched tunnelways to allow for the larger containers to fit on the more-direct Sierras route.

Today the tunnels remain empty, though still have the smell of nearly a century and a half of railroad soot. They remain Union Pacific property, and the tunnel interiors and exteriors are covered in graffiti – some visible from Interstate 80, as both the original Lincoln Highway and later I-80 travel a nearly overlapping route with the original railroad line.

The tunnel interiors have features such as drains for the snowmelt that flows into the tunnels and along the trackbed, and portions still have the electrical wires lining the inside of the tracks which would alarm the railroad in the event of rockslide severing the wire and covering the track. Though they are also showing signs of aging in the form of deteriorating concrete beams and collapsed slabs.

(you can view larger versions of the images or purchase archival prints or digital images by clicking on the link at the bottom of the page.)

View of Tunnel 6 (the 1,659′ Summit Tunnel) through Tunnel 7.

View of Tunnel 6 (the 1,659′ Summit Tunnel) through Tunnel 7.

Light falls through the wall of a snowshed connected to the far end of Tunnel 8.

Over 4 miles of covered track stretch along the Summit.

Timbers from previous wooden snowsheds lie in piles next to the concrete-constructed sheds that replaced them.

Roof segments each had four steel loops to lift them into place.

Electric wires lining the rail would signal the railroad in the event of an avalanche breaking the connection.

Avalanche warning detail.

A ceiling support beam shows the age and deterioration of the tunnels.

A collapsed section of the tunnels, the wreckage has fallen down the mountainside.

Piles of wreckage from previous snowsheds sit on the mountainside.

Donner Summit’s Central Pacific Railroad Tunnels with Donner Peak visible to the left.

(to purchase images, click here.)

or see our other blog posts here.