Godfrey Reggio

an interview with Godfrey Reggio – director of the film,

Koyaanisqatsi

spring 2011

—

[ introduction ]

On a visit to Las Vegas, Nevada, one evening I was lead into the desert. After the sun went down, we left the parked car beside the highway and set off in the direction of the river, the direction of the darkened night sky. Through washes that wound into deeper and narrower canyons, until we emerged onto the open banks of the river. We helped each other over rocks, up inclines, across sloped smoothed banks that had the moonlight glow in its orange sandy surface, and up the path of a stream that formed chest-deep pools and narrow cuts in the desert landscape.

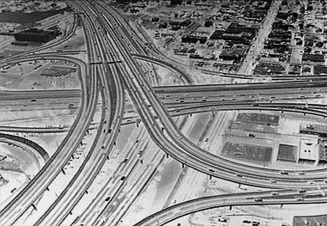

Around this time, in another corner of the country, I first saw a film called Koyaanisqatsi. An ominous film with no vocal narrative, no characters, but rather was a full-length crescendo of images set in an out-of-time fashion to a fluctuating orchestral score beginning with scenes of natural grandeur and beauty, and speeding up in pace through the chaos of urban environments, before climaxing with the descent of an exploded NASA rocket falling back to earth.

We traced the stream to its source, a hot pool in a curve in the sheer canyon walls. A pool encapsulated tightly in a wash that seasonally can govern flash floods, or, on nights like this, remain stoic, cool, echoing nothing except for the sound of the spring water running in cascades toward the ephemerally tamed wilds of the Colorado River – for tamed is only a momentary point on a spectrum unconcerned with human-scale.

Absent of a narrative, my mind reeled from the film – of the unconventionality of the film, of the images forming a picture of the alienation of industrialized environments – though, without the confirmation of this, I hesitated from what I thought might only be projecting my own ideas onto the film. But for the following weeks I carried my housemate’s VHS copy of the video in my bag and rode my bike to different friends’ houses excitedly telling them about this movie that had amazed me. The film was part of a trilogy, Powaqqatsi and the at-the-time forthcoming final film, Naqoyqatsi. Over the next several years a few interviews with the films’ director, Godfrey Reggio, surfaced. And I was taken by surprise when not only did his explanations confirm my feelings of a perspective wholly reluctant to embrace the panacea of industrial civilization, but his articulations were verbose, eloquent, and stood outside of the simplified dichotomy of technology versus stone-age primitivism.

Over the next few hours, one by one, most everyone in our group had left the springs and gone to sleep in the narrow sandy wash. Until only two of us remained. And the vulnerability of sharing these late night hours with only a stranger and a vast desert seemed to make all facades fade away. The candles we brought had burnt out, words drifted into canyon walls. And eventually the invisible ceiling of the wash revealed a narrow crescent-shaped sliver of cobalt in contrast to the black. With tired eyes we sat there until the light of morning illuminated the stone surrounding us. Then we got up, to find the others and hike out before the desert heat settled over the golden Nevada landscape.

In hindsight it seems hard to predict which moments will be as impactful as these memories are – when a walk into the Mojave night bleeds into a morning scene beyond words, or a film that years later still resonates a deluge of feeling, these two sensations that lie in excess of the sum of their parts, and to this day both hold for me a similar feeling of words and ideas and, in some ways, expectation of certain situations that give way simply to a feeling of being overcome in awe.

I sat down with Godfrey in his studio space in Brooklyn where he was several months into his collaboration with a crew on his current project, a film called Visitors. What follows are a collection of those small moments when awe overcomes the summation of words…

—

[ interview ]

Godfrey Reggio: …It’s almost as if we don’t have the language to describe what’s going on today. My main interest is language and words. I think that we see the world through language, basically, and so if the language doesn’t describe the world, if it’s describing a world that’s no longer here, which I think is the case, that’s a pretty intense statement.

We’re in a cacophony, as it were, a celebration of the ‘miracle of technology’ and so I think it’s good to have other voices out there that raise a flag or question. Not that I think my films will change the world, in any way; I think that’s megalomaniacal madness, which I’m not opposed to if it were to be efficacious, but I don’t think so. So it’s just to put this out, to have another sensibility.

Also, as a filmmaker, I’m very aware of the positive value of negation. One has to have a negative in order to have a positive. In film you have to shoot the negative, you have to expose it, it’s from that negative that something very beautiful, a positive, an image comes off. In that sense, I’ve always related, as I’m trying to say, to the positive value of negation. It’s not just to say ‘no’, it’s what that leads to. So it has a very powerful positive resonance to it I feel, but it’s not a popular point of view.

My introduction to your films was through Koyaanisqatsi, and although I was struck with how you portrayed technological society without using any kind of spoken narrative, I also was hesitant to read too much into it, I wanted to make sure I wasn’t just projecting my own feelings into the more open format of the film. Though in hearing you speak other places, I realized that yours was one of the more well-articulated critiques of this sort of modern trajectory that I’ve heard expressed.

Well I must say I’ve given up using words in the films for the reasons I stated a couple minutes ago, not for a lack of love for the language, but as I said, I don’t think it describes our world. Having said that however, all meaning in art, especially in the art I’m doing, is in the form. This is not an informational film, like a documentary, like Michael Moore’s great films have information, has a clear agenda and a point of view. It’s unmistakable, you get it and you agree or you disagree. You love the guy or you hate the guy. It makes for a good film.

In my case, if there are a hundred people that see the film, I hope there are a hundred different points of view. Because it’s a gift, it’s not a diatribe with a point of view that has the specificity of subject and predicate. It’s open to each person. So, obviously there’s much more in these films than I could put into it, and it has it’s own voice, and that’s the value of art – it speaks differently to different people. So in that sense, whatever you pull out of it is what’s there. Some people see these films as just boring, some leave right away, some see them as this or that, some see them as a celebration of technology, or, like yourself, you see it as a questioning. I mean, it’s not for me to try to explain it, it would be like, I hate to use such a heavy metaphor, but how could one explain a great painting? You don’t explain it, it’s not what it means, it’s whether it’s meaningful. Music is the same thing, it’s not what the meaning of The Four Seasons by Vivaldi is, it’s whether it was moving, if it touched you. So it has a, like a meta-language, it speaks to the spaces between words, and that’s what art can do.

I don’t believe particularly in political art because then it has an agenda, like social-realism where you’re hyping the revolution, or even the great Vertov, using all of his energy. For him the camera was more powerful in the revolution than the gun. And he was right, but it was, like, convincing you of a point of view, so it was magnificent, but propaganda. These films are not an attempt at that. They are an observation, kind of ‘what is the nature of the form in which we live?’ It’s observing the main event, like the 800 pound gorilla in the room that’s so present that no one sees it, called ordinary daily living. It’s another way of looking at the way we live; you make your own decision about what it means.

Now it’s not hard to put a very precise meaning into a film, where it’s unmistakable. Film caters to that. In fact, in the 1930’s when the US congress was considering whether to give film first amendment rights, they were really considering not doing that, and for very good reason, because they were able to see that the propaganda films of the United States, of European countries, of the Soviet Union, of the Nazis prior to the 40’s, were, like… people are very vulnerable – if it’s there it must be real, it moulds their point of view, it’s propaganda. So in that sense, we’re a fragile beast, in we can be highly influenced by image. We approach the truth through language. Mystics have always tried to see the truth, and film allows you to see things. It doesn’t mean it’s the truth however. To see the truth is a very rare, if not extraordinary, event.

How did you decide to go with the narration-less format for your films? Were there any other films that were using time-lapse and set to music that inspired you?

No. Time-lapse was used as a punctuation mark, and rarely so. It was not that prevalent, it was more like a comma somewhere, and as soon as Ron Fricke and I saw… I got a call from Ron one day and his voice was squeaking, he was so excited, he said, ‘you’re not going to believe what someone told me to go check out, this time-lapse house’. I said, ‘what’s time-lapse?’ and he explains, ‘well I didn’t know either. Anyway,’ he says, ‘you gotta see this, Godfrey, it’s going to blow your mind.’ So I went out there right away, saw it, and said, ‘we have to make a language out of this.’ So we took something that was a punctuation mark and made it the main syntax of the piece. What happened, then, was time-lapse then got picked up by every commercial art designer in the universe. Now you can’t turn on a tv without time-lapse being constantly present. And the reason they picked it up was that all these bright young people who came out of college were, of course, all bought up by advertising agencies. And they always look for, not that these were mass-made films, but they also look for people that are working with the language of image, a new way to use image, and so with time-lapse, they were like, ‘ooh, wow.’ Now there are a zillion people that do nothing but time-lapse photography and sell it to Getty Images, for example. So there is a big pool of stock footage that the world feeds on. Again, you can’t turn on a tv set for twenty minutes without seeing time-lapse footage somewhere. So it became part of the language of image. In other words, it got consumed by the beast.

What projects have you worked on in the periods of time between the making of your films?

Well here’s the thing, you know, I live in a most unusual world, for me anyway. I started out as a monk, and I became a monk-activist. I worked with street gangs, the Chicano movement, civil rights, all of that. I came to the place that I felt that I could continue that work, in a way, through trying to slip the grid with these films, that that would be another form of, not overt but covert, activism. Another way to touch people. Having said that, these films take forever to get money. Usually there’s anywhere from an eight to eleven year span between these films, sometimes a little less such as between the first and the second, but between the second and the third it was eleven years. So I spend an enormous amount of time focusing on what it is I hope to do, acting as if I’m going to do it. So I’ve had to wait a long time, I have to knock on a hundred doors to get one ‘maybe’, and in the meantime I have to keep my compos mentis about what it is I’m trying to do.

I come out of the cultural bubble of the Sixties where we didn’t think about what the future was going to be or whether we were going to have enough money in old age, or whether we’d be investing. We didn’t think about any of that. We were just living in the moment, but we lived as a tribe or a group. I work with a group of people I’ve been together with for 39 years, so I’m a very lucky person. Without that, film is so complex, it’s way beyond my capacity to do. And I work with people, in terms of the base crew, all of whom were activists before. So I spend a lot of time preparing, getting ready, having the leisure to read a lot, to go walking, and to live cheaply in the interim. That’s the key. I’m not expecting to make a lot of money here, everything I do is not for profit, I don’t want that motive to fuck up everybody’s relationships.

I set up a school for Benetton [United Colors of Benetton]. You know Benetton? They’re a clothing… empire, really. They’re huge, the first corporation to change the name from international to global. It was an enormous contradiction for a lot of my friends, that I would go there. And indeed, I was asked to go there and to create a megalomaniacal project. I was asked to create a school to smell the future. They had interviewed people in top schools all over the world to create a school, but every time they interviewed them, what they would do was create another academic institution: how would they get the students?, they would look for the ones that had all the top grades. When they asked me to do this, I told them that I thought school was the worst idea possible, that it fucks people up, that it changes their life in a negative way, in a way that’s not vital for them, and they end up earninga living rather than living. So I said I want nothing to do with it, and they said, ‘ooooh! That’s music to our ears, that’s what we want to hear, Godfrey. So where would you get the students?….’ And I said the last place I would go to would be the universities or institutions. The people in those places are somewhat institutionalized. I would look for people that are living their art, who are out there in the flow, who are not in school. Not to say that there are not a lot of bright people in school, but I wouldn’t predicate that on the basis of their grade. I said I would make a school without teachers, without classrooms, without students, where we would be in a collaborative workshop form, much like in the renaissance, and we would use the mass media windows of the world as our classroom. That’s the megalomania part because Benetton had a huge, has a huge reach. So all that after a couple, three years, came to naught. It was a lot of blood on the tracks. I learned an enormous amount, I think they did too. They’re happy now with it, but when it all fell apart, they weren’t. But for me it was worth doing. You know, I’d never get an offer like that from an American corporation. They wanted to do something special. They wanted to create like a Bauhaus. They had all these, if not, pretentious ideas, they wanted only a school for geniuses, which I told them, you know, was a ridiculous thought. And what is a genius such as the term? It’s people that live their art, who are manifestly creative and who are living it, so I recruited people from all over the world.

I work on a project for a dear friend who died in 2000, Tony Price, The Atomic Artist, who has taken all of these metals from all the bombs that were created up at Los Alamos and made beautiful art out of them. Myself and a group have dedicated ourselves to try to find a permanent home for his work. We’ve had a show at the UN, at various museums, et cetera. These are metals that would cost the ordinary folk gazillions of dollars, they’re alloy metals that are created for bombs and bomb manufacturing, and once they get a new idea, they junk all of that. It gets sold as scrap, or it used to, for fifteen cents a pound. It’s worth a fortune. And he would make these beautiful, iconic masses and statues, all made out of bomb parts.They’re very powerful.

I do a lot of lectures in order to keep my body and soul together. I’m a permanent member of the faculty at the Telluride Film Festival. I choose films, I choose all of the young filmmakers, people who are first-time students, and then present those every year. So I have a lot going on. I have a family. My kids. They’re not my blood kids, but I’ve adopted a lot of kids. I’ve got grandkids now.

And it’s true that you never went to film school?

No. I think if I would’ve gone into film school, I’d never be making these kind of films. I studied theology, philosophy, I was a teacher at the Christian Brothers. To me that was a big benefit, not to have gone to film school. My virtue is being naive really, and I think there’s something to be said for that.

It seems like, on a larger scale, a lot of us tend to fall back on, and reflect, models that we had, maybe growing up. Just what we were surrounded by, even if it’s unintentional. So you not having had any film school experience, how do you feel that that has informed your approach to the movies?

When I started making films, you could count on one hand the number of film schools in the United States, literally. It was just not there. Now every grade school, community college, university, you name it, has a moving image, or some equivalent, study group. The picture, the image, has replaced the word as our idiom, as it were. So it’s the most desirable job in the world right now, filmmaking in particular. So it’s all predicated on getting a job. Like the big feeders, for example, USC in Los Angeles. You specialize right away after you do your general courses, so you’re going to be an editor or a script writer, or a director of photography, or a director, or a lighting director, or costume, or whatever, and then it feeds you into the business of filmmaking. That’s not true all over, obviously. I mean the university of, say, South Dakota, probably has a film school but I’m sure they’re not feeding into Hollywood, unless there’s some very bright kid there, it’s hard to get into these top schools. But having said that, that’s where the jobs are today, it’s all about imaging. And it teaches you a form, and it’s usually based on getting a job. That’s true for most of the sciences, for the humanities, for everything, it’s all based on getting a job. Schools are based on jobs. Do you know Ivan Illich?

Yeah, I’ve come across a couple of his books over the years.

Yeah, he’s got two great books, Deschooling Society and Medical Nemesis, talking about how these basic human needs of what’s good for us, education, health care, or even the terms ‘education’ and ‘health care’ have been futzed with. We need to learn and we need to take care of our bodies, but radical monopolies have arisen to take care of that for us and then screw us in the process, and it’s not good for us at the end of the day to begin with. School was a perfect example. I taught school for years. I’ve spent more time dealing with the oppressive structure or form of the educational machine that I was in, rather than dealing with the joy of working with people in a creative way that maybe stepped outside of boundaries. So I think it’s the time today to question the form in which we live. It’s the form that produces meaning, it’s what we do everyday without thinking that is the real event. Marx asked this super question, he said, ‘is it the content of your mind that determines your behavior, or is it your behavior that determines the content of your mind?’ And I’ll take it from there with a homily, as it were; it’s 9 people out of 8 who answer, of course it’s our mind that determines how we behave. But it’s just the opposite. It’s what we day everyday without thinking that determines the content of our mind for almost all of us.

You bring up Illich, I feel like he verbalized these ideas that at first seemed radical, but they’re actually the most logical and un-radical ideas, they’re almost the most simple, logical ways of living or existing. But they’re so distant from what we have today.

Well you know his ideas, he was a threat not only to the establishment but to the radical left. Let me explain why. Revolutionaries, basically, were not interested in changing the form of society, they were interested in gaining the power. But if you don’t change the form, then you’re just changing who’s in charge. Look at Cuba today, it’s a fucking dungeon. I’m not putting down all the great things they’ve done, but it’s top-down, it’s like the ruler at the top, he’s a revolutionary, well what does that mean? He’s in charge rather than Batista, who was a scumbag. I don’t think Castro’s a scumbag but he’s certainly a monster. Like all other people who have to have their will over everyone else. So Ivan Illich, he was way to the left of revolutionary movements, he was a threat to them, just for the reasons you said, it’s common sense what he talks about. He was talking about something way more radical than revolution. He was talking about changing the forms in which we live, which are much more difficult to pull off than changing the power form, and we know how hard that is to do. Real radical ideas deal with changing the way in which we live, not who’s in charge.

I come from an anarchist tradition, but that’s such a difficult word to use, it’s defined by those that were its enemies: anarchists were a violent bombthrower that were going to destroy central authority. They’re not against organization, they’re not against anything reasonable, it doesn’t have to be with bombs, it just means that one has to create their own life. To me, the very essence, as a monk, of Christianity is anarchy. That’s why I was never involved in liberation theology, which was revolutionary, because the only game in town was Marxism, which is for me a new religion. You know, religion is about love, not about dogma, and Marxism is all about dogma, not about love. It’s about, you know, the right idea. Well that’s always the wrong idea. If everybody has the right idea, it’s the wrong idea. The beauty of life is its diversity.

Also, I must say that I don’t consider myself an environmentalist, even though my films have been tagged that way. My view of technology is not how it affects the environment, not how it affects politics, not how it affects religion, the economy, it’s that now everything is situated in technology. Technology is the new host of life. In that sense, technology is not something we use, it’s something we breathe, it is the host of life, it is the new environment. So technology, we keep seeing it as something we can use for good or bad. It’s bullshit I think, that point of view. It has its own politics, its own determination, its own determinants. And so it’s, how would I say, it’s become the environment of life, it has replaced nature as the host of human habitation and the rest of nature pays the enormous price for that.

Having said that, we live on a planet where there are four or five or six or seven different worlds. Bravo. What the problem is is we’re trying to create one world, one way, one idea; ‘the blue planet’. That’s a very environmental idea and I find it fascistic. To me the most fascistic image of our day is that which is hidden in plain sight, used by everyone from not-for-profits to the UN to every group, church, every social group – the blue planet itself. That image of the blue planet is the quintessential new swastika, but it’s much more dangerous because it’s embraced, it looks positive. I’m not trying to be ridiculous but I’m trying to say our world is our range of relationships, not all this heady shit about one people, one world. We have to have our own lives, we have to create our own existence. And the beauty of life is that it’s held together through diversity. So, even if it’s for ‘saving the planet’, which I’m not into, I don’t believe it’s my business to save anything, I believe it’s my business to create my own life and to live my world as my range of relationships. Now my world is the whole planet because of this madness of globalization, but it’s not human, and there’s no limit to what we’re capable of.

In regards to the third of the qatsi trilogy is Naqoyqatsi, the Hopi word meaning ‘life as war’, you’ve mentioned how technology has essentially become the new environment, how apt do you feel that the word, “war”, is in this sense?

Oh, I think it’s endemic to the way we live that ‘war’ is the predicate. But it’s beyond the war of the battlefield. It’s much more insidious, much more pervasive, and a war that appears like not war, it looks normal. I mean, we’ve gone to war with the entire rest of the planet, the animal kingdom, the vegetation kingdom, the very air of the earth itself, the vibrations within the planet, the relationship between the outer-core and the inner-core where we’re exploding nuclear devices underground for 50 years, I mean, we’re really messing around here. We all have within our bodies elements that didn’t even exist a hundred years ago, they’re ingested like the air we breathe. It all seems normal. I mean, just to support this war of living, the price we pay for this technological happiness is off the charts, and our life becomes predicated in speed, faster and faster and faster and faster. We’ve outrun our future. To me, the end’s already occurred, we’re living in the aftershock of the event, and to me that’s what I mean about being hopeless about this order, so that one can have the veracity of hope. Hope is the substance of what you hope for, it’s the only term in theology that uses the term to define itself. So it’s not just, ‘oh, I hope things are fine,’ that’s just willy-nilly. It’s the substance of what you hope for that makes hope. So I’m hopeful, but I’m hopeless.

Could you tell me about your experiences being a monk, because you’ve said that you weren’t particularly a religious person.

No, I wasn’t. I never have been, really. I’m a very neurotic person. Somehow I’m a spiritual person, but I think that’s different than the religious form. On the other hand, I think we all need community and religion is about creating community. It’s not about dogma, it’s about living in communion with other people, with love as the bind. To me, who we are is our soul. I mean, that’s what music is about. Music is Lady Atmos, Atmos is the esoteric name for the atmosphere. It’s that which we breathe, it’s around us. I’m from New Orleans, I grew up with music as a child all through my adolescence, well until the age of thirteen when I left home. That’s what the spirit is. I want to pose a conundrum: we are, both, spirit and matter. I’m sure that the spirit is concomitant with the matter, but we’re way beyond just physicality, we have something else deep inside of us, we call it ‘soul’ or whatever you want. I mean, it doesn’t matter what we call it, at the end of the day, it’s beyond… it’s not that it’s unreasonable, it’s beyond reason. I think what our mind can understand is probably this much [makes pinching gesture] compared to infinite possibility. To think that one could wrap their mind around the totality of what’s going on, that’s pure hubris.

St. Augustine on the beaches of North Africa was pondering the meaning of god, of existence, of the universe. He was walking up and down the beach going nuts. He saw this little kid, and he got really taken, and this little child had built a big hole in the sand carved out of a place about this big [gestures with arms], and he had a little bucket and was going over to the sea and was bringing the water in, into the hole. And so Augustine said, ‘what are you doing there, kid?’ And the child said, ‘well you know, I’m going to put all of that water here in this hole’, and Augustine laughed at it. And the kid said, ‘I’ll fill up this hole before you figure out what’s on your mind.’ Whether that’s a real story, it doesn’t matter. it gets the point, that we have a real limit to what our capacity is, that makes us who we are, it gives us a certain fragility and indicates our clear relationship and need for love. It’s who we are. You know, we’ll never figure it out, it’s just not in the cards. So in that sense, I do miss my religious community.

In regards to the film you’re currently working on, how has your approach to filmmaking changed or evolved over the years?

I’m not interested in, or probably capable of, making a real movie. I’ve discovered a form that I’m really locked in with now that I love. Though I don’t want to keep repeating myself, so I’ve introduced into this film narration as a point of view – though it’s non-spoken narration. It’s the narration of body language, facial display, eye behavior, gesture.

The first rule of cinema – there are exceptions of course, but that only proves the rule – is that the actors never look directly into the eye of the camera, except with extraordinary exception, in order to keep the illusion of this voyeuristic event taking place. You’re sitting in a black room watching the most intimate, from death to love to comedy, taking place as if these people are not aware of you, like you’re peeping through the hole. I want this film to be in dialogue with the audience. I want to bring the audience in. So all the people that we’re looking at are in direct eye contact with the audience at all times. And the setting, as it were, is between the real and dreamstate. The dreamstate, of course, all of our dreams are colored with the metaphors of life – in other words, nature, people we know, buildings, stars. This is who we are. Our dream world is populated with the images of the daytime, so they’re nighttime images bathed in the light of day, let’s say. But then at the moment we wake up, you’re right in that twilight zone between the real and the dream, and if you’ve had a vivid dream, you’re not sure of what’s real. In this film, we’re looking for that moment where there is this confusion between the real and the dreamstate. I’m looking to confuse reality and dream.

It’s going to go out with a live orchestra. The qatsi’s have been performed live now over 250 times. We still have a little more shooting to do. And then get the venues and go through all kinds of ideas and see everyone’s schedules to be able to perform it live like the others. But this one’s going to be different from the other ones. It has a different feeling.

—

Visitors was released in 2013. More information about viewing and purchasing the film can be found here.

Information about viewing and purchasing Koyaanisqatsi can be found here.